|

Author Profiles 2007:

Part One: Cold Water, on the Way to Clarity FRANK GREGORSKY: Elizabeth, I was thrown for a loop by your Nonfiction Book Proposals Anybody Can Write. That book had a profound impact on me, and here's the single passage that was the bucket of cold water: "The biggest mistake writers make is to start writing too soon, before they've done any planning or organization or additional research. That process begins with deeper examination of your idea, of its merits and marketability, and of your writing skill." ELIZABETH LYON: Right. GREGORSKY: Your book then offers many examples of how a book proposal should [explain and market] the idea to a publisher. Suddenly -- like within five seconds -- I realized that the past three manuscripts I've helped people with [names deleted to protect the unpublished] -- these writers did exactly what you warned against, and I didn't know enough to stop them from producing the entire bloody manuscript! You have left those of us who want to publish something or say something [to a wide audience] with no excuse: If we want to get the thing out and have a publisher, and have at least a couple hundred people, if not a couple thousand people, take it to heart, we have to do some version of what you're saying in that book. It was a life-changing moment. LYON: Well, thank you. And the process of producing a proposal brings its own changes. All my editing clients who've wanted to get their nonfiction books published -- every single one of them -- ended up with a different book, a different slant, or a better book, or a clearer concept, after they finished the proposal. They thought they already had something firm. Then they went through the proposal process, and ended up with something better -- refined, slightly different, but better.

LYON: Yes! Yes -- in some cases. GREGORSKY: And we're talking about a database of how many? You've seen this play out with how many people? LYON: You mean how many clients? Why, I've never counted them. Let's say -- of nonfiction [pause] -- boy, that's stopping me [pause]. I'll pick a number: 200, 300. GREGORSKY: Wow. Now count the completions [manuscripts that became real books] on your website -- if you throw in the novels, the number is around 50. LYON: Yeah. GREGORSKY: Which means the other 150 [using your first guess of 200 clients] did not get a publisher. LYON: Yeah. Probably. GREGORSKY: Okay -- [a ratio that] is daunting in itself. LYON: That includes people writing memoirs, which is just about one of the most difficult kinds of nonfiction to get published. But what happens in the process -- the proposal process -- is that by being forced to define some very definite topics that have to be answered, and that the person never thought about, they rethink the whole project. GREGORSKY: Yet they're still in control. It's not like they're submitting something [in a random way and] getting their ideas torn apart. In a funny way, it should turn into an empowering type of thing -- because [the would-be author is] still doing the thinking and the researching and the modifying. LYON: Right. Like for instance, almost everybody fails to do an adequate search of the competition. In the past, it was Books in Print. Now we can go to Amazon. To flush out what has been done, put in a sufficient number of synonyms; then look on the inside of the book, read the table of contents, check the index, and read a sample of the writing. And so what I do as an editor -- with everybody now -- is go to Amazon and take a look. Almost always, I'm coming up with other books, and saying, "Well, how is yours different from this one?" And "it looks like this area has been covered. What do you think about that, and how could it change your plan?" This leads to a discussion and a shift. For example, most people's titles are inadequate and not very good. And I think titles are enormously important -- not just for sales, but for the person to grab hold of as a touchstone for their work. GREGORSKY: Even though any title is likely to be changed later. LYON: Even though it might be changed, yep. Because it -- GREGORSKY: It's a gyroscope of sorts. LYON: It is. It also [helps you keep to a] tone. For slant, tone, and with content, [a good working title] can be the North Star for the project. Almost always, out of this interaction between the two of us, a title will emerge. GREGORSKY: Need to ask you about resistance. Of course, if someone has already hired you, they want you to help in some manner. In other words, they can't be too resistant or locked-in. But -- how hard is it to sell what you're saying, to sell the process of "don't write the manuscript yet" and "hold off"? LYON: [10-second pause] People approach me at different stages. Some clients use my services at a very early stage: "I thought of writing books on this topic, that topic, and this other topic. Which one do you think has the most promise?" So we have a very early discussion. They don't have a book. They don't even have a firm idea, much less any pages. And will that become a book? It's hard to say. So that's one form of client. Other people might have a couple of sample chapters, and it's still "very warm clay." There's not a figure emerging very strongly -- and again, that's easier to work with. GREGORSKY: And there you have some evidence of seriousness, because they've produced something. LYON: Right. Right. GREGORSKY: The first category could be somebody who's just totally speculating. LYON: Yes. After an initial discussion or a couple discussions, or a little bit of working together, let's say I get somebody to send me a summary, a concept statement -- anything, in writing, about their book. Then I can give them some direction. It's really best if they come back to me next with a rough draft of the proposal. People who say, "Well, can't we do a section at a time?" -- my experience is that they don't finish. They do not finish. GREGORSKY: They'd prefer to do a section at a time of the proposal? LYON: Yeah. Like the piano lesson: "Give me a schedule, and I'll give you this..." Rarely works. The only time I can think of when it did work was with a former journalist who's used to deadlines. Part Two: Entering the Lyon Den -- Who and How? GREGORSKY: How long do you give someone to put together a whole draft proposal? LYON: I don't. No time limit is set. GREGORSKY: You just say, "Bring me a complete draft." LYON: Yes. GREGORSKY: Get them to swallow the whole thing -- or commit to swallowing the whole thing. LYON: Yeah. Or it works the other way around -- which is fine with me. Let's say I have a sense that they have a good idea, a worthy idea, one that could sell in the marketplace. They may have no background as a writer, but they might be a good writer -- I don't know until I see their writing. And we'll mutually decide: "Send me some of your chapters first, before [we start on] the proposal." So the proposal process does not necessarily come first. If we start with some of the chapters, I'll really know where they are in the writing. So it can go in the reverse direction -- especially in memoir. In memoir, I'd really prefer to see the writing and a summary. GREGORSKY: If the odds are so long [for legitimate publication], why do you mess with memoir-writers? LYON: Because my job, as I define it, is not only to work with writers whose works stand a chance to get published, but to help everybody. I occasionally weed somebody out for other reasons, but [the operating principle] is to help everybody [pause] make their dream come true. If they have the desire to complete a book, and nowadays we have a lot more ways that a book can get published, I try to help them figure out whether it's a possibility for Plan A. Of course, most people start with, "I'd like to see if this [idea or manuscript] can be represented and sold to a large publisher." If it looks like, by qualifications and what they have to offer, it could go that direction, then we go for it. But if the author doesn't have that, then I start talking about plan B or Plan C or Plan D. GREGORSKY: Your Plan A candidates -- would you say that one out of every four prospects or clients get there? Meet those strainers? LYON: [Pause] It differs from year to year. This year? One in four? Yes. Yes. And I'm not sure what produces the waves, but sometimes we'll get a wave of people who really are not going to make it, and other times their projects are incredibly exciting. GREGORSKY: What would a Plan B look like? LYON: Plan B is to seek publication with a small press or a smaller press where possibly -- probably -- an agent's not gonna be involved. And the person can directly query an editor, which sometimes is a great idea -- but then the person has no platform. If they get their book published first with a smaller, perhaps dedicated, press, they could aim for a second book to be with a larger press. GREGORSKY: Umm-hmm. LYON: This is a "paying your dues" kind of order. And Plan C is a smaller press, or a regional or specialty press, or something even smaller, [which means] less distribution. And then Plan D is print on-demand, and I especially recommend www.Lulu.com. GREGORSKY: Saw a Forbes article about them about a year ago. LYON: Because Lulu will do it for free. And -- that's a good price! GREGORSKY: [Laughs] Does anybody come in and say, "I just want a book. I want to say what I want. I'd like you to help me clean it up a little bit -- but this is just for family, friends, my business colleagues, and some buddies I golf with. I only need 300 copies, and I don't really need to make money." LYON: Sure, definitely. Yep. I get those clients, too. Maybe all they want is copy-editing -- essentially, clean it up for grammar, punctuation, "and then I'm gonna publish it [so] don't change any of the ideas." If they don't want "developmental" or organizational help, and they just want a copy-editor, I subcontract it. I've been very lucky to have this editor in Eugene that I've been training for maybe 10 years. She wanted to learn nonfiction book-proposal editing. And we do team-editing. She does the first edit on a work; sends it back to the writer; and they revise it. (She also writes an evaluation, 15 to 20 pages long.) They send back their revised version. And I do the second editing, which we hope will be the last. They pay one fee for all that.

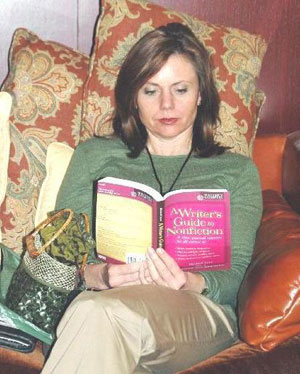

GREGORSKY: Do you take on a client simply because the topic is so interesting? Even if that person might be a little bit disorganized or half-committed or whatever, you feel that "this is a new one" -- here's somebody trying to innovate, somebody trying to dig? LYON: [Pause] Well, I probably have accepted 98% of everybody who calls me and wants help! GREGORSKY: Really? LYON: I don't use much of a sieve. My philosophy has been to try to help everybody improve -- and I feel like my editing is strongly instructional. So they might not be able to achieve what they hope for (which is that Plan A). But, if they want to follow the advice and revise, they'll end up with a decent book. GREGORSKY: Umm-hmm [nods]. LYON: And so I haven't been exclusive. Occasionally I've thought, "I wonder if I should do that." Basically the clients I would eliminate are personalities I don't want to work with; or if I get too busy, then I'll say: "Here are other editors who can help you." GREGORSKY: And when people show up with a completed manuscript and say, "Oh, I just want you to help me get a publisher," you obviously have to talk them through several things at that point. LYON: Yes. Because it doesn't work that way -- they need the proposal. And so that shifts the whole process towards this device, out of which they're gonna see that they need to reshape what they wrote. GREGORSKY: Maybe it's rare, but how about a situation where a completed manuscript [was worth your diving into]? LYON: If I accept and work on a finished manuscript -- well, here's a case from last year: A psychologist who already had the book accepted. Working on a deadline, she felt she needed an editor. Her editor at the publishing house didn't want her to work with a book editor, fearing that [this additional editor] would impose their ideas on it. But the writer felt like she needed some help, and her agent recommended me (because I'd worked on another project for a psychologist for that agent). And we ended up with a one-month deadline. She was writing chapters as I was editing them. The organization of the chapters was a mish-mash. She was a good writer, with good content, but had to re-shift the outline of all the chapters into a different [scheme]. GREGORSKY: Okay, yet another situation. A family reunion is coming, and I'm independently wealthy and just want to write a check and get a bunch of books [to distribute there]. Apart from a situation like this, is a fair comment -- given print on-demand, whether it's Lulu.com or some of the earlier attempts at it -- that there really is no case anymore for paying a huge [per-copy] amount to get 500 books, just because "I want these books and I'll have them in my garage while I try to sell them"? LYON: No, there is a case: Back-of-the-room sales. This would be people who are speakers, and already have established circuits. GREGORSKY: Yep -- good. No other case besides that? It's hard to think of. LYON: Hard to think of [pause]. Some novelists in my critique groups know about print on-demand but have chosen to have old-fashioned print done -- it's partly, or mostly, a function of their age and discomfort [with print on-demand]. GREGORSKY: Wary of those mystical, less-than-tangible digital processes. "How do we know they'll spell it right on the next 20 copies?" That sort of thing. LYON: Yeah, yeah [laughs]. Part Three: Another Lyon Book for Realists GREGORSKY: Okay, Elizabeth, now we're going to talk some about your 2003 book, A Writer's Guide to Nonfiction. It has a very clear cover, and I love it when book covers don't try to get clever or mysterious. The sub-language is "A clear practical reference for all writers of essays, memoirs, biographies, how-to, self-help, technical, features, articles, profiles, Q&A, travel, food/recipes, outdoor, nature." Let's jump to the fourth chapter -- "How Can I Refine My Idea?" -- where you talk about slant. "Slant" is a kind of a slangy general word, and here you're using it as an umbrella to cover the 15 most common slants. So this is your Charles Darwin [mode of] categorizing all the different species. LYON: Well now, I -- GREGORSKY: You got some more? LYON: I was influenced. I don't make up all this out of my mind. You know, I do my research. GREGORSKY: I know! But you came up with all these names. LYON: Well, the originator of the list from which I drew and then added to is Lisa Collier Cool. And she wrote a book that I think is the best book for nonfiction article-writers (magazine and newspaper articles), called How to Write an Irresistible Query Letter. GREGORSKY: Umm-hmm, umm-hmm. LYON: And she had a list of slants. GREGORSKY: How close is that to this [list of yours]? LYON: Very close. I have some different names on some of them, and think I may have added a few. But [my list is] very close to hers, so that's not original with me. GREGORSKY: For purposes of the transcript, I'll list all 15 slants -- because some terms, on the face of it, they don't tell you exactly [what the essence is]. Or course, you do that inside the book! But we're producing a conversational prompt here.

I like the way you spin NEWSY: "This slant lends itself best to newspapers, websites, and publications that are part of the ‘immediate media.' In this slant, the subject itself is the slant." Even that phrase "immediate media" makes me split the print media into things with and without a time lapse. All of the slants, as noted, are explained in the book. For now, though, maybe you can elaborate on PROMISES. LYON: Whether it's in an article or with a book, you make the promise to the reader that you're going to fulfill some need they have. It can be as seemingly superficial as "double your money." Read this book and you'll be able to double your income -- well, that's a promise. GREGORSKY: Umm-hmm. LYON: It's a pretty outrageous promise, but there's a promise slant. Double your money, or double your real-estate holdings -- anything like that. One that came out in recent years -- and of course it had a numbers slant [in addition to the basic promise] -- was how to meet a man you'll marry in two weeks. Or maybe it was two months [laughs]. But -- that's a big promise. Inquiring minds should be a little suspicious of big claims, big promises. But [the "promise slant"] can be used for superficial things, or it can be used as a slant for profound and meaningful works. GREGORSKY: "Profound and meaningful works"? Part Four: Political Advocacy versus Methodical Need-Fulfillment LYON: By writing the piece, what difference are you seeking to make that's in harmony with your values? This can often get to the core of how a writer wants to change the world, wants to leave a legacy. In what particular way? GREGORSKY: That phrase "change the world" is one I've heard most often among political activists. If you're in favor of welfare reform, or some other public policy stance, and you honestly think it's going to benefit people, then you could say to yourself: "Yes, I want welfare reform because I think it's going to help taxpayers, welfare recipients, whatever." LYON: Umm-hmm [nods]. GREGORSKY: But I think that's a little different. If I have an idea for a political change, then obviously I think it's good for the country. But isn't a tighter test for me to be able to declare that "my book will help this slice of America live better"? LYON: Yes. GREGORSKY: Or invest better, sleep better -- whatever. LYON: Yes. Yes. What really gets writers in trouble is when they begin a project from the viewpoint of "I'm going to write an article on this because I can get $2,000 if I sell it to Playboy magazine or to Harper's or -- " GREGORSKY: Harper's pays two grand for an article? LYON: No, no. They might! -- I don't know now. But targeting a higher-end publication so they can get paid $1,000, $2000 -- if they're thinking in terms of "what I'm going to get" from it, then it's not going to be as strong as if they're thinking: Who's my audience? What do they need? What's a need that can I fulfill? GREGORSKY: That's it! Is that stated like that in here? "A need I can fulfill"? LYON: Yeah, that's kind of in the earlier part [of the book] rather than the chapter that covers slant. GREGORSKY: Okay. LYON: But [that principle] goes with the slant. I mean, you pick some to mesh together. GREGORSKY: And "types of slant" is not just how to write a good lead. It really is fundamental to the whole piece. LYON: Yes. Yes -- and every book does make a promise. I mean, that's kind of a little different from the "promise slant," but it can be the same. Every book has a promise to the reader. "I will supply what I've promised." In my case, "I will show you how to write a book proposal that will be a successful book proposal" -- you know, there's a promise, right in the title.

GREGORSKY: Where I come from [politics and cause-oriented journalism], a lot of books are just people sounding off about political views or -- LYON: Well, that's true -- okay [laughs]. But I don't read those books! GREGORSKY: Well, those are the ones I've been tasked with. But -- I guess the implicit promise is "if you'll elect me, you'll get better government." Yet that's not really a "promise." Isn't it much more like a premise? A default setting on the part of anyone confident enough to try to win high office? LYON: Yes. Yes, I agree with you. And my orientation has not been towards your audience. It's been more toward the general public, so I can see where -- you know, shift the audience and you might not have that these factors come out so much. GREGORSKY: Well, see, that's why I like [this discussion], because my problem is that friends and collaborators and long-time political allies want to write a book so they can sound off about these ideas or recommendations. Now I will know what to run them through: Not just who will buy this, but exactly who will be helped by buying this. LYON: Yes. Yes. GREGORSKY: That's a different way to pitch it! LYON: It is. It's very different. And by the way, one other thing -- something that was said by a mentor of mine. He was a language analyst and a futurist, and a brilliant man. You could apply this to any experience in life, but [just stick with writing]. He said, "If a piece of writing makes no difference to the reader, it has no meaning. The very definition of meaning is that it makes a difference." So, if somebody sounds off, and a reader reads it, and it hasn't made any difference to them, it really has no meaning. GREGORSKY: I need to quibble here. In the world of ideas and intellectuals, "difference" is not necessarily a matter of "I'm going to motivate you to go out and either change your personal behavior or start a soup kitchen" or something tangible like that. "Making a difference" [in the world of concepts and government can be] "I've changed your perspective on things." LYON: Umm-hmm [nods]. GREGORSKY: It's purely a mental thing -- a mix of philosophy and perspective. Would this be [part of your mentor's standard for] "making a difference"? LYON: Oh, I see. Okay. GREGORSKY: Well, that's what intellectuals do. They're not trying to get you to do anything. Maybe a radical activist book might say go out and bomb the Pentagon. But most books in Washington -- LYON: Yes. GREGORSKY: -- are trying to change your view of an issue. LYON: Okay. They're persuasive. GREGORSKY: Right. LYON: They're arguments or persuasions. Well, and I guess -- yes, [such books and articles] would make a difference, if they're accomplishing that. Part Five: Teachers and Parents Don't Buy the Same Book GREGORSKY: The examples [you suggested we add for this second taping are] of people who showed up at your door with completed manuscripts or partial manuscripts. LYON: Right. Or [they showed up with] what they thought were complete ideas, or with substantial portions written. GREGORSKY: And then we'll hear some of the ways you consulted around them. LYON: I remember one example. A woman taking one of my classes had written a book on parenting. Her intended readership was parents with children from ages one to 18. I had to break the news to her that, "Who's going to buy that book?" The parent of a teenager will have no interest in how to get a kid potty-trained -- the parent has been through that. So such a book would not [appeal to that] broad of a range. She didn't realize that she was going to have to select an age range. GREGORSKY: There aren't enough moms with large traditional families that might range from ages two to 15 -- LYON: Yes, that's right. GREGORSKY: -- at any given point who'd want that book. LYON: And if they do [have a big family], they've probably figured out all the answers to parenting and/or have their older children taking care of the younger children [laughs]. This just never dawned on her. GREGORSKY: Great example. That's the kind of insight that saves the would-be author from a blurred focus right at the start. LYON: Here's one that's more subtle. Another client had co-authored a book with her daughter. Her daughter was a pre-school teacher, or maybe a teacher in the early grades. The mom worked as an administrator in a hospital. And the daughter had developed all kinds of activities to do with young children that would teach them environmental awareness, ecology, respect for nature. GREGORSKY: Seems reasonable so far. LYON: And this was way before all of that became so central; we're going back maybe 15 or 20 years -- environmental activities you can do with your kids. This mother and daughter thought [they had crafted] a good book for both parents and teachers. It would give teachers a whole repertoire of things to do with kids in the classroom -- pre-school, first grade, second grade, around that age -- and parents could do most of these same things with their kids at home. So it seemed very reasonable that it would be useful to both of those audiences. GREGORSKY: Umm-hmm [nods]. LYON: However, parents would [be made to] feel immensely guilty by the quantity of activities and exercises. It was just an overwhelming number. GREGORSKY: They'd suddenly see all the things they weren't doing -- and feel bad? LYON: Yes. On the other side [of the audience, the] teachers would want the author to not explain things as thoroughly as she did -- because teachers already know a lot [of ways to organize kids]. GREGORSKY: Right. LYON: So the parents would've needed a smaller version and more explanation, and the teachers less explanation and more activities. GREGORSKY: That's great. Perfect statement of a mal-design in the original marketing premise. LYON: And it failed as a project. This was also part of my learning curve at the time, because I thought it would be a wonderful book. I hadn't caught that distinction between the two different markets -- teachers [versus] parents -- and that they couldn't be blended. GREGORSKY: How did that awareness emerge? LYON: It was the mother who took one of my writing classes. She had learned how to write a query letter, which is what she would need to market the book. And she had mailed it out -- maybe, I suspect, out of a little bit of disbelief as to whether these letters really do work -- to something like 15 publishers. Agents and publishers both! And she gets back 14 replies saying, "Please send the proposal." Well, this woman and her daughter have the book ready; and [they've been marketing with only] the query letter. No proposal yet. And I hadn't yet caught that distinction between the two different markets, and how they couldn't be blended. But the immediate issue is: "What now? I've got all these requests, and I don't have a proposal!" You don't want to have them waiting too long -- GREGORSKY: No. LYON: -- and, though I still think it's remote that nonfiction ideas are stolen, it is possible that they get inadvertently shared, and an idea ends up in the hands of someone who can develop it. So the point is not to wait too long. Well, I had one agent friend [that the writer had] sent the query to. She calls me up and says, "This book won't fly." But the author is racing to develop the proposal. It's summertime, so I get her to send a note to all of the people who requested it, telling them that she's working on polishing the proposal, and that she'll have it to them by Labor Day. So she writes the proposal. My agent friend asks which publishers [it has been sent to], I tell her, and she says: "Oh, that one is known for stealing ideas." GREGORSKY: Ohhh. LYON: At any rate, I think the author sent it to this agent first. Partly because she's a parent, her reaction to the proposal is: "I read this and feel guilty. I feel guilty that I won't be serving my children well unless I do these activities -- at least a small percentage of them. But I won't be able to do even a small percentage of the quantity that's in this book." She is explaining the dual market to me. Parents and teachers rarely can have a book for both of them. GREGORSKY: Umm-hmm [impressed]. LYON: So there's another case. GREGORSKY: That's great -- a hugely valuable [design] insight. Part Six: Self-Help Readers and How-To Readers LYON: The travel narrative in various forms is certainly a popular form of book. A lot of people are travelers, and travel produces all kinds of interesting experiences (for some people more than others), including who they have access to. And if they fancy themselves a pretty good writer -- well, why not? Why not write a book on it that could get published? GREGORSKY: That's their logic or that's your logic? LYON: That's their logic. GREGORSKY: I'm waiting for the skepticism [laugh]. LYON: I've also had people wanting to write their life stories in one form or another, because they've had a famous, noteworthy career; or based on some dramatic event in their lives; or -- GREGORSKY: They assume this would be a real book that thousands of people might be interested in? LYON: Yes, of course. Oh, definitely! Many people have had very successful careers and would like to share their expertise. They want to pass that expertise on in their area. It includes a lot of stories about how they encountered this problem, and "don't go that way, do this instead" -- and there is a wealth of experience in people who have, in any area of business, done well. A lot of times, what will happen is a person will really want to write about themselves. GREGORSKY: I am shocked. LYON: They had these experiences, and they learned, and "isn't this wisdom valuable?" Ummmmmm yes, it's valuable. Actually, there's no question that it's valuable. However, how-to books for other people, and even informational books, just rarely work -- seldom work, almost never work -- GREGORSKY: [Laughs] LYON: -- when the examples are solely from the authors. It ends up coming across as egocentric and narrow, and just one person's experience. GREGORSKY: It's the same thing with a business book. Here's some hotshot on how to build a multimillion-dollar corporation. And the guy's basically telling his own story over however many years. He thinks he understands entrepreneurship, but it's a career story. And probably not a bad story -- yet it's not generic. You can't carry it over to another industry, or to the current generation. LYON: Yes. Yes. And of course everybody's interested in a celebrity biography or a celebrity memoir, and would read it because of the celebrity. But, when it's somebody who's not a celebrity -- GREGORSKY: So how do you break the news to somebody who comes in eager to produce one of these? LYON: Well, I tell them what the structure is. Either one -- the structure of writing how-to, or the structure for self-help. And then we discuss: What does your reader need? I have a little phrase [that sums up] the self-help reader. This might not fit the how-to reader, but the self-help reader is "needy and greedy," and they want the focus to be on me-me-me-me. GREGORSKY: Yeah, yeah. Exactly. LYON: And so they don't want the author to tell long stories. They want to get their problems and issues resolved. So get back to the instruction [format] and have a lot of examples. You hope that one example will fit the demographics and situation of that reader and another [will make sense to] the next reader. GREGORSKY: Umm-hmm [nods]. LYON: Yes, the author's experience can be in there, but briefly. Otherwise the person really wants to write a memoir -- which is a different form and should never be mixed up with a self-help or a how-to. GREGORSKY: And the memoir can be vastly simpler, too. Nearly all the examples come from the writer's own "war stories." LYON: Umm-hmm [nods]. GREGORSKY: If it's a self-focused account, they can hire me [to do a family audio history] and arrange those stories on a CD, or they can produce a small, family, friends, colleagues, old business buddies, type of book. LYON: Yes. Yes. GREGORSKY: Three hundred copies and that's it. The entire project can be done in six months. LYON: You also asked, and I hadn't quite answered -- because maybe you were edging around [the topic] -- do I ghostwrite? Or do I participate with somebody in writing their work? I wasn't sure if you were asking that earlier. GREGORSKY: No, but -- let's ask it. I might have said the word "collaboration" -- which sent the wrong signal [by sounding like a form of ghostwriting]. LYON: Okay. GREGORSKY: By "collaboration" I really meant aggressive coaching. Which is not the same. But, sure -- let's say somebody wanted you to ghostwrite their book. LYON: So far, I've said no. I'm going to ghostwrite a proposal this summer. But it's for a colleague who has written a wonderful book; it's on how to write memoir, and I have edited it. GREGORSKY: You aim to get a book published on "how to write the memoir"? Well, that helps solve one of your problems -- because you're tired of people doing it the wrong way [laughs]. Part Seven: Don't Start off Trying to Do a Linda Ronstadt GREGORSKY: My favorite business and marketing author, Al Ries, likes to quite Confucius: "Man who chase two rabbits catches neither." His books also stress how vital it is to help the prospective buyer "categorize" the product or service. Unless you've got ‘em locked in a conference room, that part has to lock in almost immediately. You know -- is it "animal, vegetable, or mineral"? On the web, most people won't invest more than 20 seconds to figure that out. When someone can't convey what they are offering and how it works, why would you trust them to be able to deliver it? Let's consider a case or two where the very "nature of the beast" is confused. LYON: Okay. Well, right now, I have a client who's trying to extract what her book really should be. She started out sending me some chapters. She didn't have the proposal done yet, but she was working on it. "Okay, I'll take a look at the chapters." As far as I could tell, it was a memoir. It starts with her early childhood experience in her family, and her conflicts with her father and [pause] a touch of his -- not physical abuse but emotional abuse. So I think it's a memoir. But she also wants to offer how-to advice. Blending the two is complex. GREGORSKY: Her profession is?

LYON: She's a motivational speaker, and that can be a problem. GREGORSKY: Weakness on the content side. Being professional speakers, what does [their historic training] mean for their writing? LYON: Most of the time, they don't understand organization,

specificity of detail, and the need for diverse examples. Usually, they

simply cannot write. Then I recommend a ghostwriter. LYON: Very interesting perspective -- and I agree. Of course, there are also people who do both well -- public speaking and writing. I can only ask the question: Are these kinds of speakers transporting an imaginary audience into the process of their writing, but with enough realism and variety of people to anticipate what a reading audience needs? As I ask this question, it strikes me that this must be a sophisticated skill, or a natural talent. Yet, I know people who do well in both venues. I fear [laugh] I may be one of them. GREGORSKY: Well, I doubt any professional speaker will be sifting through the Q&As at ExactingEditor.com. So let's steer back toward your experiences with going from idea, to proposal, to manuscript, to a product that satisfies some slice of a market. LYON: I would just say, in a general way, some people may have done a substantial part of the writing -- but they don't know what it is they've produced. GREGORSKY: Back to animal, vegetable, or mineral. LYON: Right, and there's no "fault" there. But having completed a book, which is a monumental achievement (and yes, it's great to finish), they think it's ready to publish. In fact, most of the time, it's a rough draft! It's raw material. The next step is to extract from that what the book really is, and how it needs to be put together if they intend it to have an audience [pause] beyond Mom. GREGORSKY: [Chuckle] LYON: So, with many people who have written a lot of their book, that's were the recognition is lacking. They don't have that recognition. GREGORSKY: What is the common -- if there is a common -- reaction or "processing" of that when you get it across? LYON: A lot of times, this doesn't happen face to face. It happens on the phone, or it happens through them receiving my evaluation of what they've sent me. GREGORSKY: So they call back -- three months later. LYON: I'm not there for the weeping and gnashing-of-teeth part, most of the time. Sometimes I'll get back somebody who is defending -- what I call intellectual sparring -- underneath which are some strong emotions. So I'll have to convince them, and ask a lot of questions, about their intention for the piece -- asking questions to determine which form they are trying to fit. GREGORSKY: Right. LYON: And if they haven't had guidance on form and outline, and the different categories, a lot of times they haven't read across category. They might be highly knowledgeable about one type of book, but then they [produced a manuscript] that's not completely that type of book, and it goes into another category. In the industry, that's called crossover -- a crossover book. GREGORSKY: Just like in the music business. During the 1970s, Linda Ronstadt might be on both the pop and the country-western charts with the same song. LYON: Or here's an example of one woman who was not a client, but she let me use her proposal and her story for the proposal book. A California therapist (I think she was a therapist) wrote a book about gardening as a meditation. She got it published, but it did not deliver good sales. She even got an Oprah. With her own mix of marketing pursuits, she got her material in a [staff] file [of people] hoping to get on the show. She lucked out. They decided to do a show that in some way featured, I guess, the healing benefits -- GREGORSKY: Because Oprah likes to bring on categories of practitioner -- three at a time. LYON: Yes. Yes. And still the book didn't sell well. I talked with her: "Do you think the problem might've been that it was a crossover book, and therefore didn't have one strong market?" And she agreed -- she thought that was the case. GREGORSKY: What was the gap her manuscript was trying to stretch itself over? LYON: When you think about it, there are people who love to garden and would buy a gardening book, but not relate at all to meditation. And there are people that meditate who are not at all interested in spending time out in the garden. GREGORSKY: One type is sort of off in the netherworld and the other prefers the physical, the tangible: Do this, plant this bulb, grow this plant. LYON: Right. And then you have -- you do have an audience that is like [this author]. They understand gardening, and they love the spiritual aspect. But the other two audiences [focused gardeners and committed meditators] are either not going to buy the book, or they'll be uncertain. They'll be pretty uncertain. GREGORSKY: There must've been some place to go, though -- a specialty magazine, TV series, certain websites -- for that admittedly small group (maybe it's only 50,000 people) that are the crossover practitioners: Gardening plus meditation. LYON: Yes, and since this book came out [pause] probably in the early ‘90s, and here we are 15 years later, she may have been about 10 years ahead of the curve. GREGORSKY: Yeahhh. Now the early boomers are retiring. They want to putter around out back, yet still be part of the vast cosmos. LYON: And so we have those kinds of books. You can have a financial version [of that crossover] -- investing in the stock market as a meditation. It makes you feel good [laughs] -- when you win! But everything has been blended with spirituality. GREGORSKY: Absolutely. LYON: And so therefore, it could've been a book ahead of its time, in terms of grabbing enough of a market. |

||||||||

You know

how easy Internet research is. You know how simple it is to circulate electronic

text. And you've heard how book sales continue to slough off the supposed

threat from iPods and TV. So why not write a book? Because having the

manuscript published is a struggle all its own.

You know

how easy Internet research is. You know how simple it is to circulate electronic

text. And you've heard how book sales continue to slough off the supposed

threat from iPods and TV. So why not write a book? Because having the

manuscript published is a struggle all its own. GREGORSKY:

GREGORSKY: